History of the Australia Indonesia Association

The Australia Indonesia Association grew from the Indonesian Club formed in George St, Sydney in 1942. The organisers included a group of Indonesian petty officers stranded in Sydney during WW2. They conceived the idea of an Indonesian / Australian association to support Indonesian independence. The inaugural meeting of the AIA was held on 3rd July 1945 at the Odd Fellows Hall, 145 Castlereagh St, Sydney.

An AIA committee was chosen from the packed room. University of Sydney Professor A. P. Elkin became its first President. He had a strong belief in the Atlantic Charter which promised self-determination to countries under colonial administration. The first Secretary was Molly Warner.

Molly later married an Indonesian, Mohamad Bondan. Mohamad and Molly returned to Indonesia to become involved with the setting up of the 1955 African-Asian Conference in Bandung.

Eight of the original committee of 18 were women. Two of these were, Mrs L Reid and her daughter Charlotte (Lottie) who later married Petty Officer Anton Maramis from the Indonesian Club. After the war, Lottie followed Anton to Indonesia. In Jakarta, they opened Indonesian Observer, the first English-language newspaper in Indonesia.

Enshrined in the first minutes were the aims of the association: To promote friendly relations with a region of which Australians have little knowledge, yet a region that will play an important part in Australia's sphere of foreign affairs in the post-war world.

Funds raised from the initial membership of 150 were used for printing publications and pamphlets promoting Indonesia's right to independence.

Another campaign supported Indonesians stranded in Australia during WW2. By the end of 1946, all the stranded Indonesians had returned to Indonesia. An influx of Indonesian Colombo Plan students from 1956 led to a rekindling of interest. A Sydney businessman and President of Sutherland Shire, Seymour Shaw, reinvigorated the AIA with the original aims and objectives intact.

AIA associations were also started in Victoria, South Australia, the ACT, and Queensland.

Indonesia-Australia History

The AIA has been involved in several projects over many years related to events which helped shape the relationships between Australia and Indonesia. These have included:

Plaque commemorating the support for Indonesian independence.

History walks in Sydney

Cowra

Camp Victory - Casino (NSW)

Our thanks to Dr Stephen Gapps, Curator of the Australian National Maritime Museum, for the following article published in the ANMM Blog

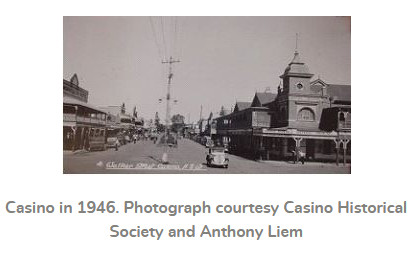

On October 24, 2015 the AIA assisted in organising a gathering of over 100 people in Casino in Northern New South Wales to commemorate the 70th anniversary of an event not widely known in Australian history. In late 1945 residents of the sleepy rural township of Casino were dramatically drawn into the events surrounding the struggle for Indonesia’s independence from the Dutch.

After the Japanese invasion of Indonesia in 1942 the Dutch, who had been the colonial power in Indonesia for over 300 years, fled to Australia. The Dutch Government in exile brought with them Indonesian soldiers, sailors, government officials and others.

From December 1943 a few hundred Indonesian soldiers arrived in Casino as part of the Dutch Armed forces Technical Battalion. They trained and worked in preparation for the Dutch return to Indonesia when the war was over.

Although Australia was still under the race-based immigration restrictions of the White Australia Policy — and these soldiers would not have otherwise been allowed in the country — it was wartime, and they were part of the Dutch armed forces.

The soldiers also had soldiers’ pay, and after work hours finished would they visit the small township of Casino. Apparently they were good business in the local shops — many long-term Casino residents recalled them buying bicycles and having a fondness for perfume. They also remember the soldiers showing them how to make and fly kites.

At the end of the war in August 1945, the army camp in Casino had become known by the Dutch as the Victory Camp. Between 1943 and 1945 other elements of the 10,000 Indonesians who had arrived in Australia with the fleeing Dutch government began to arrive at the camp. Some of these were anti-colonial Indonesian nationalists who had been imprisoned by the Dutch, who thought they would be a danger if left behind in Japanese controlled Indonesia.

But tension was to grow in the normally sleepy township best known at the time for its dairy industry. The first word of the Indonesian declaration of independence reached Camp Victory in September 1945, and along with it came orders from the new Republic to ‘defy the Dutch’. By 12 September many of the soldiers declared they were no longer under Dutch jurisdiction. They were hastily imprisoned by the Dutch guards and almost overnight Camp Victory was surrounded by floodlights, watchtowers and a barbed wire fence.

Indonesian sympathisers in Australia — mainly from the left-wing maritime trade unions who had black banned Dutch ships returning to Indonesia — began to publicise their plight, some describing Camp Victory as a ‘little Belsen’, akin to a Nazi prison camp. During the next few months many of the Indonesian soldiers around the country refused to obey the Dutch and were promptly shipped to Camp Victory to be court martialled. By October there were around 400 prisoners. They sent a letter to the Prime Minister on 29 November explaining they were no longer Dutch subjects and demanded release.

But they were court martialled by the Dutch and received prison sentences. While their plight increasingly came to the attention of the public and activists such as Molly Warner were writing to the Prime Minister, they continued to be imprisoned throughout 1946.

After two deaths in the camp — one possibly a suicide — on 12 September guards opened fire at a protest by the Indonesians. One defiant ex-soldier named Soerdo was shot dead and two others wounded. Sympathisers, Casino residents, the press and now the Australian government were outraged.

By October the prison sentences of the first 200 ex-soldiers had ended and they were released, discharged from the Dutch armed forces and sent to Brisbane for repatriation back to Republican-held Indonesia. While the Dutch further incensed the Australian government by secretly transferring 13 of the ‘ringleaders’ out of the country, by December the remaining 300 prisoners were released.

Pak Konjen and Ibu Konjen from the Indonesian Consulate in Sydney were guests of honour at the seminar. Historian Jan Lingard was the main speaker and members of Casino Historical Society and Grahame Irvine from Southern Cross University in Lismore provided background information on the Army Camp and the Indonesian soldiers.

The seminar re-visiting these events from 70 years ago on 24 October 2015 was jointly organised by the Australia Indonesia Association (AIA), the Casino Historical Society and the Richmond River Council. The forum created much interest with about 100 people in attendance including some long term Casino residents who remembered the infamous Camp Victory and the Indonesian prisoners.

A visit to the site of the camp provided an opportunity for some of them to talk about their recollections of the camp from 1943 to 1946. Many remembered the Indonesian soldiers who refused to serve the Dutch very well and some had in fact became good friends during this period.

As historian of the period Jan Lingard wrote, the Casino events saw the Indonesian Revolution come to an Australian country town. In a strange and largely forgotten twist, this sleepy rural township in northern New South Wales was where some of the first Indonesian blood of what was to be a long and protracted war to maintain independence, was spilt — far from Indonesia, on Australian soil.

— Dr Stephen Gapps, Curator

Further reading:

Jan Lingard Refugees and Rebels: Indonesian exiles in wartime Australia Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2008.

An Englishman goes Makassan

G E P ’Pat’ Collins 1904–1991

Whatever happened to this Oxford drop-out after he ran away to the East, found love and a passion for ’native’ sailing, became a best-selling author and built his dream boat – a Makassan prahu? Museum research associate Jeffrey Mellefont pieces together a forgotten life.THE MAKASSANS OF THE INDONESIAN ISLAND called Sulawesi are of special interest in the study of Australia’s pre-colonial contact history. They were a ship-building, seafaring and trading people who had centuries-old, commercial and cultural relations with Aboriginal societies during annual fishing voyages to Australia’s northern coasts. Their chief catch was trepang, edible sea slugs that abounded in the shallows of Arnhem Land and the Kimberley. Starting long before British settlement, Makassans dried and smoked the trepang on Australian beaches, sailed home on the monsoon winds and traded them on to China where they were a prized delicacy believed also to be an aphrodisiac.

This story of cooperation between Indigenous communities and seafarers from the Indonesian archipelago is the first that visitors encounter in the museum’s new exhibition Under Southern Skies.[1]

When I first began researching Indonesia’s diverse, unique but little-recorded maritime traditions, 40 years ago, information was hard to come by. But in the State Library of New South Wales, I encountered two remarkable books published in the 1930s about the Makassan clans of South Sulawesi and their distinctive sail-trading craft, or prahus. East Monsoon (1936)[2] and Makassar Sailing (1937)[3] were written by a young English adventurer who had lived and sailed with the fierce Makassans of the remote and arid south-western peninsula of Sulawesi – the island widely known as the Celebes during colonial times when the Dutch ruled the East Indies.

In East Monsoon the author, G E P Collins, relates his experiences voyaging as a guest on a Sulawesi trading prahu called a palari pinisi in the Makassan language. He relishes the utterly spartan life under sail with no engine, no safety or navigational equipment and no comforts, living on rice and dried fish cooked over a wood fire in a kerosene tin. The book introduces the Makassans’ seamanship and Muslim culture as Collins negotiates to have them build him a palari pinisi of his own.

The subsequent volume, Makassar Sailing, details life in this traditional Islamic boat-building society: its stories and folklore; religion, magic and superstition; piracy, warfare and conflict. It’s a district where Dutch colonial authority scarcely extends. We read of Collins’s trials there, dealing with malaria & dysentery epidemics and with wiley, sometimes cheating and uncooperative boat-builders. He records the communal ceremonies of building and launching prahus and the ancient, pre-Islamic spells and rituals that were essential for a ship’s welfare.

The 1930s fleet of trading palari

pinisi running under dry-season

skies. Previously unpublished

G E P Collins photograph,

Leiden University Library special

collections

This was a time when the English-speaking world knew little about the many diverse cultures of the Netherlands East Indies beyond Java, and next to nothing about maritime Makassans. Such information, where it existed at all, was in Dutch-language field reports and journals. Collins, a sympathetic and involved observer of his Makassan hosts, was a keen amateur ethnographer. As well he was a superb photographer, capturing the essence of these people, their seamanship and the timeless cycles of their seasonal, monsoon-wind trading voyages. For a long time, these two handsome, richly illustrated hardcover books were the only detailed, English-language studies of this maritime culture that once played a significant role in Australian history.[4]

Makassar Sailing includes Collins’s own design drawings of the local trading boat that he ordered, with the yacht-like coach house he added for improved accommodation. These were shipwrights who had never seen a plan, sculpting their prahus by eye to proportions based on the human body. At last his boat was launched, costing a total of 590 Guilders or

£80 fully rigged... a bargain price, in his era, for a ‘yacht’ 53 feet (16.2 metres) overall length and built of solid teak. He called her Bintang, which means ‘star’.[5]

But the two-book series ends with that launching, so that generations of readers and researchers have wondered whatever became of Collins and Bintang. They disappear from sight. Why nothing more about his voyages from this prolific writer? Did misadventure

befall his ship?

01

At sea on the trading palari pinisi

Mula-Mulai Muslim seafarers can

perform their obligatory daily

prayers anywhere, kneeling in the

approximate direction of Mecca.

Previously unpublished G E P Collins

photograph, Leiden University Library

special collections

02

A study in Makassan seamanship;

backing the mizzen to help push the

bows through the wind while tacking.

G E P Collins photograph published

in East Monsoon 1936

Library catalogues revealed one earlier book by Collins, a novel published in 1934 called Twin Flower: a Story of Bali[6]. It’s more of a rambling travelogue than a novel, with its long expositions of Balinese village life and customs. Curiously, it’s illustrated by many of Collins’ accomplished, National Geographic-style photos, some of which depict its supposedly fictional Balinese characters. This leads readers to suspect it’s autobiographical... but

where did the fiction end and real life start?

The book’s protagonist, an Englishman called Garland, declares himself from the first page to be one of those outcast colonialists who rejects the conventions and racial prejudices of his fellows and is happy to ’go native’. We first meet him in Singapore, about to embark for Bali on board a cockroach-infested Sulawesi sail-trading prahu whose nakhoda (captain) is an old friend.

In Bali, Garland mixes with both simple fishermen and aristocrats of the north-eastern kingdom of Karangasem while learning how to sail the fishermen’s jukung – the lateen-sail, outrigger fishing dugouts that can still be found there today, 90 years later. The tide-ripped waters of the strait between Bali and the neighbouring island Lombok are his training ground.

The peculiarities of English culture are contrasted with Balinese traditions in lengthy dialogues between Garland and his native friends (speaking together in the East Indies traders’ and sailors’ language, Malay). Just when the ’novel’ seems close to ending, still searching for a plot, it introduces a sensational cross-cultural affair between Garland and a young Balinese girl called Mas (’Gold’). This would have been confronting for many English readers of the period… no less than Collins’s photo of her, showing her topless.

03 Galley in a kerosene tin, the cook

blowing the wood fire embers.

Previously unpublished G E P Collins

photograph, Leiden University Library

special collections

01

G E P Collins’s cruising ‘yacht’

Bintang was based on the

seven-sail Makassan palari

pinisi trading ketch, with some

minimal accommodations added.

Previously unpublished

G E P Collins photograph,

Leiden University Library

special collections

02

Collins’s Makassan crew toast

their voyage. They feature

individually, by name and nature,

in Komodo: Dragon Island: centre,

wearing the hat, is boatswain and

chief steward Hoedoe. Previously

unpublished G E P Collins

photograph, Leiden University

Library special collections

Mas is an outcast too, banished from a royal Balinese family since she has a twin brother. In many Indonesian societies such a birth is feared as an incestuous disaster, threatening the natural order of things. Exiled into a Lombok fishing community, Mas is also a skilled jukung sailor. Garland woos her afloat and they have a sailing honeymoon round Lombok’s gorgeous coastline. It doesn’t end well, with a sudden, shocking, tragic fate for Mas and her royal twin brother Rai. Garland gets off quite lightly and shrugs it all off as native adat or custom.

The timing of Twin Flower, published in 1934, was perfect. A craze for exotic, bare-breasted Bali, the ’Island of the Gods’, was stirred in the 1920s–30s by a series of celebrity visitors including anthropologist Margaret Mead, actor Charlie Chaplin, and some high-profile film makers, artists and musicians. The novel sold very well and helped to finance Collins’ Makassan prahu-building venture in Sulawesi – as well as boosting sales of East Monsoon and Makassar Sailing when they appeared soon after.

Twin Flower threw some light on Collins’s previous East Indies travels and his intense interests in local people and their sailing traditions – quite unusual in the colonial context where ‘natives’ and their activities were generally considered inferior. But the fate of the man and his Makassan prahu Bintang remained a mystery. Until an email from Belgium crossed my desk at the Australian National Maritime Museum some 70 years later. It was from a Dutchman called Rudi van Reijsen, who said he was Collins’s nephew. He had inherited all his late uncle’s archives, which included a manuscript written by Collins in the late 1930s about his voyages on Bintang, as well as many unpublished photographs. In 2003 Mr van Reijsen self-published the posthumous manuscript, with a selection of photographs, in a limited, 330-page paperback edition of 100 copies. Its title was Komodo: Dragon Island.[7]

He was contacting our museum to ask if we wished to buy a copy. You may imagine how quickly I ordered some.

His uncle, it transpires, had hired a crew of six Makassans and sailed Bintang to the islands of the Komodo dragon. The crew included a cook and enough hands to man the oars, his engineless prahu’s only auxiliary power if the wind failed or currents were contrary in these difficult, reef-strewn waters.

Collins had initially aimed for the Moluccas further to the east: the original Spice Islands, source of the precious cloves and nutmeg that had first lured Europeans to the Indies. But the eponymous wind of his earlier book title, the East Monsoon, was blowing hard and it forced them south to Sumbawa, hundreds of kilometres across the Flores Sea. With difficulty they reached the island of Komodo where the eponymous dragons lived.

There Collins spent six months studying and photographing Varanus komodoensis (called ora in the local language), with the same passionate curiosity that he had applied to his Makassan hosts in Sulawesi. The large carnivores were little-known at that time, and Collins disproved some wildly inaccurate published reports that the dragons were seven metres long and ran on their hind legs like Tyrannosaurus rex. Nonetheless they grew to nearly four metres and could prey on careless villagers as well as their usual diet of wild pigs and deer. Collins used the rotting carcases of chickens and goats to lure the dragons within camera range.

Living on Bintang and mixing with local Bajau sea-gypsies, and Manggarai hunters from the nearby large island of Flores, he explored the Komodo archipelago with his customary relish. The harsh life and poor nutrition he endured in this remote, dry, rugged ’paradise’ led to illness and infection that put him in hospital in the Dutch regional outpost of Ruteng, Flores,

in 1937. There he met a Warner Brothers team hoping to film this ’lost world of prehistoric creatures’, and he ferried them to Komodo on Bintang.

Komodo: Dragon Island paints an unvarnished picture of Collins. He was a lively writer but one who had benefited greatly from the highly professional editors of his London and New York publishers in the 1930s. The manuscript finally published by his nephew is unedited, preserving all the idiosyncracies and excesses of its often quixotic author.

In a foreword, nephew Rudi van Reijsen wrote a brief biography of the man he called his ’favourite uncle’. It answered many of the questions about Collins’s life that I had harboured for decades. In 2016 I was able to visit the elderly Mr van Reijsen at his home in Brussels, to find out even more about his uncle.

George Ernest Patrick Collins was born in India on 17 April 1904, but was sent to England as an infant and brought up by a relative. In an introduction to his final book, ’Pat’ (as he called himself) describes a childhood obsession with ancient ships and the tropics: Caravels off palm-fringed shores, in a picture book given to me on my fourth birthday, made me want one of those old sailing ships...When I read about ancient Greek, Roman and Carthaginian ships they displaced the caravels. The tropical attraction grew stronger

as I learned about Indonesia, the world’s largest archipelago.

Collins read Greek, Latin and Ancient History at Wadham College, Oxford, in 1923-26, but perhaps distracted by his obsessions he failed his final exams, so he couldn’t get a foreign service job. Instead he joined the Blue Funnel Shipping Company and was posted to Penang and Singapore as a shipping agent. He learned to speak Malay, met South Sulawesi sailors trading to Singapore and fell in love with their prahus, which had double side-rudders like ancient Greco-Roman ships and high sterns like old Portuguese caravels.

In a foreword, nephew Rudi van Reijsen wrote a brief biography of the man he called his ’favourite uncle’. It answered many of the questions about Collins’s life that I had harboured for decades. In 2016 I was able to visit the elderly Mr van Reijsen at his home in Brussels, to find out even more about his uncle.

George Ernest Patrick Collins was born in India on 17 April 1904, but was sent to England as an infant and brought up by a relative. In an introduction to his final book, ’Pat’ (as he called himself) describes a childhood obsession with ancient ships and the tropics: Caravels off palm-fringed shores, in a picture book given to me on my fourth birthday, made me want one of those old sailing ships...When I read about ancient Greek, Roman and Carthaginian ships they displaced the caravels. The tropical attraction grew stronger

as I learned about Indonesia, the world’s largest archipelago.

Collins read Greek, Latin and Ancient History at Wadham College, Oxford, in 1923-26, but perhaps distracted by his obsessions he failed his final exams, so he couldn’t get a foreign service job. Instead he joined the Blue Funnel Shipping Company and was posted to Penang and Singapore as a shipping agent. He learned to speak Malay, met South Sulawesi sailors trading to Singapore and fell in love with their prahus, which had double side-rudders like ancient Greco-Roman ships and high sterns like old Portuguese caravels.

George Ernest Patrick Collins was born in India on 17 April 1904, but was sent to England as an infant and brought up by a relative. In an introduction to his final book, ’Pat’ (as he called himself) describes a childhood obsession with ancient ships and the tropics: Caravels off palm-fringed shores, in a picture book given to me on my fourth birthday, made me want one of those old sailing ships...When I read about ancient Greek, Roman and Carthaginian ships they displaced the caravels. The tropical attraction grew stronger

as I learned about Indonesia, the world’s largest archipelago.

Collins read Greek, Latin and Ancient History at Wadham College, Oxford, in 1923-26, but perhaps distracted by his obsessions he failed his final exams, so he couldn’t get a foreign service job. Instead he joined the Blue Funnel Shipping Company and was posted to Penang and Singapore as a shipping agent. He learned to speak Malay, met South Sulawesi sailors trading to Singapore and fell in love with their prahus, which had double side-rudders like ancient Greco-Roman ships and high sterns like old Portuguese caravels.

Collins read Greek, Latin and Ancient History at Wadham College, Oxford, in 1923-26, but perhaps distracted by his obsessions he failed his final exams, so he couldn’t get a foreign service job. Instead he joined the Blue Funnel Shipping Company and was posted to Penang and Singapore as a shipping agent. He learned to speak Malay, met South Sulawesi sailors trading to Singapore and fell in love with their prahus, which had double side-rudders like ancient Greco-Roman ships and high sterns like old Portuguese caravels.

01

The autobiographical novel Twin

Flower: A story of Bali (1934) has

photographs of its supposedly

‘fictional’ characters including

this one of the protagonist’s

romantic interest, the Balinese

exile Mas.

In 1929 he resigned his desk job and took passage from Singapore to Bali on a Makassan-built trading ketch or palari pinisi, just like Garland in the ‘novel’ Twin Flower that followed. Whether Collins actually had an affair with the Balinese girl in the book’s photo, his nephew Rudi van Reijsen couldn’t tell me. He did explain that after the Komodo adventure, his Uncle Pat had sailed Bintang back to the port of Makassar and laid her up on a beach.

In 1940 Collins married a Dutch airline employee, Lida van Reijsen, in Batavia (Jakarta) where he found work in the British Consul-General’s information bureau.In February 1942 the couple barely escaped the invading Japanese with their lives, as evacuating ships were bombed. They reached the United States via Australia and New Zealand. As an expert on the East Indies Collins worked for the US Offices of War Information and Strategic Services, aiding Allied plans to retake the islands.

In wartime USA Collins lectured about his Indonesian experiences. An article he wrote for the January 1945 edition of National Geographic, called ’Seafarers of South Celebes’, earned him a tidy US$500 – several times more than he had spent on building and crewing his prahu Bintang.

After the war Collins didn’t return to the East Indies, which was briefly re-occupied by the Dutch until international recognition of Indonesian independence in 1949. He had received news about Bintang from the Dutch harbourmaster of Makassar, who wrote: ’...on account of

bombing and machine-gunning [during Allied air strikes], the hull of the vessel is a total loss and not worth repairing’.

It seems likely that World War II and subsequent post-colonial conflicts were the reason why this prolific writer’s Komodo: Dragon Island went unpublished during his lifetime. His London publisher probably received the manuscript about the time that war with Hitler began. After the war, Indonesian struggles against the Dutch and the turmoil of Indonesia’s early decades of independence made the story of a young English vagabond’s curious adventures in a pre-war Dutch colony somewhat dated or irrelevant.

Collins had a post-war career in various United Nations agencies, becoming an expert on aquaculture for developing countries. He and his wife Lida had no children, retiring to Florida where Collins died in 1991 at the age of 87. His widow, the youngest sister of Rudi van Reijsen’s father, died in 2000.

02

Pat Collins and his wife Lida van

Reijsen in the USA in the 1940s.

Photographer unknown

G E P ’Pat’ Collins was an unusual, quirky ’colonial’ for his time, an enthusiast for the sailing traditions, cultures and islands of what we now call Indonesia – then the East Indies or Malay Archipelago. He’s been something of an inspiration to me, in that respect.

I have often visited the boat-building beaches of South Sulawesi where Collins’s prahu Bintang was made, including on several ANMM tours where I introduced museum Members to the Makassans. [8]Their shipwright traditions are still thriving, hand-building prahus of solid teak or ironwood beneath the coconut palms. Indeed, much larger, modernised, motorised versions of Collins’s palari pinisi are built there today as tourist charter or dive boats.

It was my good fortune to meet Rudi van Reijsen just a few years before he died, aged 91. I was eager to see what other unpublished Collins photographs there might be; some of them appear here, for the first time. Not long before my visit, Mr van Reijsen had donated Collins’s entire archive – negatives, prints, manuscripts, field notes and correspondence – to the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, a noted research centre fo Dutch colonial history and Indonesian ethnography. Fortunately for me, he had kept digital scans of the photographs, which he shared with me.

The archive will become a rich record of pre-war maritime Indonesia when, in due course, it has been catalogued by the University of Leiden and made available to researchers.

Author Jeffrey Mellefont was the founding editor of Signals 1989–2013. In retirement he continues to research, write and lecture on the history and seafaring traditions of Australia’s archipelagic neighbour, Indonesia.

[1] Makassans as well as Bugis, Butonese, Mandar and Bajau (Sea-Gypsy) people took part, trading trepang through the major Sulawesi seaport Makassar. These related seafarers, all from Sulawesi, are grouped under the Anglicised term ‘Macassans’ in the seminal study, The Voyage to Marege by Campbell MacKnight, 1976 Melbourne University Press.

[2] G E P Collins, East Monsoon, 1936 Jonathan Cape, London;

1937 Charles Scribner Sons, New York. All the Collins books are

available in the museum’s Vaughan Evans Library.

[3] G E P Collins, Makassar Sailing, 1937 Jonathan Cape, London; 1992 Oxford University Press, Singapore

[4] Annual Makassan fishing voyages to Australia were banned by Australian customs and immigration officials in 1906. Collins would have met living veterans of these voyages, 30 years later.

[5] Collins’s prahu was based on the principal Makassan trading ship of the 20th century, with its Dutch-style gaff rig. A model of their earlier ships, which had no such Western influence, appears in the exhibition Under Southern Skies. See the author’s essay on the evolution of Makassan prahus at sea.museum/2018/01/24/unesco-heritage-lists-indonesian-

wooden-boat-building/

[6] G E P Collins, Twin Flower: a Story of Bali, 1934 Jonathan Cape, London; 1992 Oxford University Press, Singapore

[7] G E P Collins, Komodo: Dragon Island, 2003 Editions Clepsydre, Brussels: limited edition of 100

[8] See Jeffrey Mellefont, ‘Members in Makassar’, Signals No. 108 September–November 2014 pp16–21

[2] G E P Collins, East Monsoon, 1936 Jonathan Cape, London; 1937 Charles Scribner Sons, New York. All the Collins books are available in the museum’s Vaughan Evans Library.

[3] G E P Collins, Makassar Sailing, 1937 Jonathan Cape, London; 1992 Oxford University Press, Singapore

[4] Annual Makassan fishing voyages to Australia were banned by Australian customs and immigration officials in 1906. Collins would have met living veterans of these voyages, 30 years later.

[5] Collins’s prahu was based on the principal Makassan trading ship of the 20th century, with its Dutch-style gaff rig. A model of their earlier ships, which had no such Western influence, appears in the exhibition Under Southern Skies. See the author’s essay on the evolution of Makassan prahus at sea.museum/2018/01/24/unesco-heritage-lists-indonesian- wooden-boat-building/

[6] G E P Collins, Twin Flower: a Story of Bali, 1934 Jonathan Cape, London; 1992 Oxford University Press, Singapore

[7] G E P Collins, Komodo: Dragon Island, 2003 Editions Clepsydre, Brussels: limited edition of 100

[8] See Jeffrey Mellefont, ‘Members in Makassar’, Signals No. 108 September–November 2014 pp16–21

Baits of rotting carcases lured

Komodo dragons into camera range.

Previously unpublished G E P Collins

photograph, Leiden University

Library special collections

THE INDONESIAN GRAVES AT COWRA N.S.W

( By Jan Lingard, author of “Refugees and Rebels”)

( By Jan Lingard, author of “Refugees and Rebels”)

During the extensive research I carried out for my book ‘Refugees and Rebels:

Indonesian Exiles in Wartime Australia’ I discovered that a number of Indonesians had

been interned in the Cowra P.O.W camp in 1943 , and that some of them, including

women and children, had died there. The first group were striking merchant seamen on

Dutch ships, and the second group comprised Dutch political prisoners and their

families, brought to Australia from the notorious jungle prison at Boven Digul in then

Dutch New Guinea. These people were nationalists, incarcerated by the Dutch for their

efforts to gain independence from their colonial masters.

After more research I found a record of those who had died and the dates of their deaths.

I contacted Cowra Council to ask if anyone knew of Indonesian burials in the local cemetery and then went to Cowra to look for the graves. With the assistance of Graham Apthorpe from the Council, I located the graves, identifiable at that stage by the only grave with a headstone which bore the name ‘Salamah’, whom I knew to be one of the women who died. The graves were just slabs of discoloured concrete, side by side, marked by rotted wooden posts which may have had names on them back in the 1940s when they were erected

I was anxious to identify who was buried where, and in the Cowra courthouse archives I found records of the deaths, including the dates of burials, which were in chronological order. I wondered why one grave had a proper headstone so I visited the local stonemason and learned that after the war, Salamah’s son had visited Cowra to have that headstone erected on his mother’s grave. I’m glad he did because by knowing the date of her burial, I was able to identify who had been buried in the other graves.

I felt that this was an important find and visited the Indonesian Ambassador of the time, Bapak Wiryono, to inform him of my discovery and discuss the possibility of the graves being restored as befitted Indonesian freedom fighters. Wiryono was able to persuade the Indonesian Government to do this, and with the co-operation of the Cowra Council in 1947, the graves were restored to the impressive state we see today. And those who died are no longer anonymous.

After more research I found a record of those who had died and the dates of their deaths.

I contacted Cowra Council to ask if anyone knew of Indonesian burials in the local cemetery and then went to Cowra to look for the graves. With the assistance of Graham Apthorpe from the Council, I located the graves, identifiable at that stage by the only grave with a headstone which bore the name ‘Salamah’, whom I knew to be one of the women who died. The graves were just slabs of discoloured concrete, side by side, marked by rotted wooden posts which may have had names on them back in the 1940s when they were erected

I was anxious to identify who was buried where, and in the Cowra courthouse archives I found records of the deaths, including the dates of burials, which were in chronological order. I wondered why one grave had a proper headstone so I visited the local stonemason and learned that after the war, Salamah’s son had visited Cowra to have that headstone erected on his mother’s grave. I’m glad he did because by knowing the date of her burial, I was able to identify who had been buried in the other graves.

I felt that this was an important find and visited the Indonesian Ambassador of the time, Bapak Wiryono, to inform him of my discovery and discuss the possibility of the graves being restored as befitted Indonesian freedom fighters. Wiryono was able to persuade the Indonesian Government to do this, and with the co-operation of the Cowra Council in 1947, the graves were restored to the impressive state we see today. And those who died are no longer anonymous.

.JPG)

Indonesian graves at Cowra

History of Indonesian graves

Indonesian graves

.jpg)

Jan Lingard and Siti Chaminsah

Indonesian graves

The Great Escape from Boven Digoel

( By Budiman BM)

( By Budiman BM)

Boven Digoel is in a remote location in the middle of Papua jungle used by the Dutch to settle exiled prisoners. It is hundreds of km upstream of the Digul river, in the middle of remote jungles, hot and humid, and malaria-infested.

Communists, nationalists, dissidents who took part in anti-colonial uprisings against the Dutch, or who had too openly opposed colonialism were sent to Digoel for internment.

There was no barbed wire or watch towers, but Boven Digoel was surrounded by jungles and rivers full of crocodiles. The jungles were scarcely populated by Papuans who were still cannibals.

There were sixteen escape attempts from 1929 to 1943. Most of them unsuccessful. Some died or hunted by Papuans.

In 1929, a group of internees successfully escaped through the fly river and reached Thursday Island in Australia. But the Australian government contacted the Dutch and they were sent back.

The group led by Sendjojo was the only successful escapee. It was a great escape as they had to walk a month in the jungle about 100 km to the river. They were 22 days on the boat sailing through the Fly river to get out of Papua. After that it was still 250 km to Thursday island. He told his adventure in a letter forwarded to the Malay Chinese newspaper “Keng Po”. The story was soon reproduced by Malay and Dutch newspapers in March 1930.

Approximate escape route from Tanah Merah to Thursday Island (green line) about 900 km

Here is the transcript:

Melarikan diri dari tempat pemboeangan.

Minggat dari Boven Digoel tertangkap di Queensland

Soedah lama kita merasa tidak enak tinggal ditanah pemboeangan. Tidak lantaran kita biasa tinggal senang, tapi ada banjak peratoeran jang bikin kita ingin meninggalkan Boven Digoel dengan djalan apa djoega.

Sebab-sebabnja tidak perloe kita toetoerkan dalam pemoelaan ini toelisan.

Begitoelah kita dengan berampat pada satoe hari soedah ambil poetoesan boelat boeat melarikan diri. Masing-masing manaroh soempaeh boeat setia disepanjang djalan. Hidoep satoe, hidoep semoea, mati satoe, mati semoea.

Kita poenja bekal

kita biasa seperti orang-orang lain, kendati pada hari Saptoe tanggal 20 Juli 1929 kita soedah ambil poetoesan akan melarikan diri. Kira-kira djam setengah toedjoeh sore kita soedah beroentoeng terlepas dari pergaoelan teman-teman lainnja dan pendjaga dari interneeringskamp.

, Sendjojo dan Diposoekarno dari Solo, Koesmeni dari Djokja dan D. Abdoerachman dari Pontianak itoe sore soedah koempoelkan bekal jang perloe boeat samboeng djiwa di perdjalanan.

bekal ada 3 blik beras, 30 pak tembako “Warning”, 30 bidji kertas sigaret “Club”, 2 pak besar roko Djisamsoe, 1 compas ketjil, 1 horloge, 3 doos besar korek api dan 4 bidji kampak ketiil.

tanah tinggi jang letaknja dengan kapal “Urania” ada berdjalan 10 djam disoengai. Kita- orang soedah menobros djalan dihoetan lebat jang kira-kira beloem pernah diindjak orang sopan. Di sepandjang perdjalanan tidak gampang, selain toemboehan sebagai alang-alang jang tinggi,rawa jang boeajanja dan dipohon2 sering kelihatan binatang boeas, djoega sering kali kita bertemoe dengan orang Papoea jang masih terlandjang boelat.

Keabisan makanan

Berdjalan kira-kira 20 hari persediaan soedah habis.

Tembako masih ada tapi basah semoea dan hantjoer lantaran hoedjan. Beberapa hari barang lainnja bisa ditoekar dengan sagoe, zonder omong, pada orang Papoea jang ketemoe didjalanan dalam hoetan, tapi tidak lama lagi barang toekar itoe djoega soedah habis. Terpaksa kita makan iboeng, boeah boeahan, akar-akaran toemboeh-toemboehan jang boleh dimakan.

Rongkongan manoesia

Kita berdjalan teroes sekoeatnja dan searahnja. Beberapa kali kita sampai di kampoengnja orang Kaja-Kaja jang masih boeas. Marika poenja badan ada koeat, sebagai anak natuur jang toelen.

Banjak jang badannja lebih besar dari orang-orang di Java. Diantara marika ada jang badan atawa moekanja, ditjat pakai loempoer atawa getah poehoenan sehingga berwarna merah atawa hitam: kepalanja dihijasi dengan boeloe boeroeng Paradiys, hidoengnja di lobangi tengahnja dan pakai sioeng (slagtanden) dari babi hoetan.

Disatoe kampoeng lagi kita ketemoekan segoendoekan toelang rongkong manoesia, ada jang soedah lama kering dan ada jang masih berdarah. Sekali kita orang soeda diraba-raba kita poenja badan, sedangkan rombongan jang dibelakang toekang raba itoe ada pegang sendjata. Oentoeng kita tidak diboenoeh, sebab apa kita tidak tahoe, marika poenja bitjara satoe sama lain kita tidak mengerti.

Pada satoe malam sedangkan kita sama tidoer di bawah poehoen ada lagi orang Papoea boeas jang sampari kita.

Oenteng kita lantas bangoen, hingga itoe orang batalkan maksoednja, dan lantaran kita diperlindoengi oleh Toehan, itoe orang lantas kasih sagoe boeat makan pada kita.

Schoonheyt, 1936. Boven-Digoel.

Schoonheyt, 1936. Boven-Digoel.

22 hari diatas sampan

Sesoedah kira-kira satoe boelan dalam hoetan, ditepi soengai ”Fly” kita ketemoekan serombongan orang kampoeng (Papoea jang manis boedi).

Zonder satoe sama lain mengarti kita dapat makanan dan pemondokan dibawah atap dari daoen-daoenan, Kita tidak maoe menjoesahkan itoe orang, menjebabkan pakaian kita boeat toekar-dengan satoe sampan. Itoe tawaran marika terima baik dan kita dapatkan satoe sampan.

Dengan girang dari ketetapan hati kita teroes naik itoe sampan menoeroet djalannja itoe kali dengan pengharapan sampai dilaoet. Tjoema kadang-kadang djikalau lapar soedah tidak ketahan lagi kita mampir didaratan boeat tjari apa sadja jang boleh dimakan.

Schoonheyt, 1936. Boven-Digoel.

Ditangkap dan didenda

Dengan pertoeloengan alam kita soedah sampai dimonding (pengabisan) soengai Fly. Dari pasisir lain kita dan lihat perahoe-perahoe ketjil lainnja dan tidak djaoeh antara itoe satoe poelau jang kelihatan ada roemah-roemah serta banjak perahoe kelihatan di pasisirnja. Kita menoedjoe ke itoe poelau, jang belakang ternjata masoek dibawahan pemerintahan Australie.

Di itoe poelau ada beberapa kantor, dan satoe kesalahan bagi kita, kita soedah mintak pekerdjaan (o’ darah kaoem boeroeh) di itoe kantor. Satoe orang Inggeris lantas tanjakan kita poenja paspoort, dan kita tjoema bisa djawab dengan angkat poendak. Kita lantas ditahan dan paginja dimadjoekan depan depan magistraat lantaran mengindjak itoe tanah zonder toelatingssbewijs. Poetoesan dari itoe kehakiman, kita didenda masing-masing 100 pondsterling atawa f 1200.- djadi ampat orang f 4800.

Astaga! Dari mana oeang sebegitoe sedangkan sepeser tidak poenja. Lantaran kalau tidak bajar itoe dendahan dihoekoem badan 6 boelan masing-masing, kita soedah pasrah sadja pasang badan.

Dalam boei di Queensland kira-kira satoe boelan.

Herankan keberanian kita

Kita mendengar kabar, orang-orang di Queensland sama herankan keberanian kita. Sajang kita orang boeron, kalau kita termasoek expeditie tentoe kedatangan kita disamboet dengan muziek? Orang-orang Inggeris sendiri bersama 40 orang tidak berani berdalan di Fly. Sebab orang Papoea disitoe terkenal terlaloe boeas dan soeka makan manoesia mentah-mentah.

Lain dari pada itoe satoe sama lain kampoeng masih bermoesoehan heibat/ Orang asing datang gampang disangka sebagai perkakasnja atawa spion dari lain kampoeng, risikonja besar sekali. Kita berampat tjoema tinggal pakaian robek dan sendjata empat, kampak ketjil jang tidak kita lepaskan kalau tidak bersama-sama dengan djiwa kita. Tjoema kita beloem sampai pada nasib moesti mati, kendati sewaktoe-waktoe dalam tahanan boei di Amboinia kita sering kepingin mati dari pada hidoep.

Kembali djadjahan Belanda

Sedang kita meringkoek dalam tahanan reepanja didjalankan correspondentie antara pemerintah Queensland dan Molukken begitoelah waktoe tanggal 27 October pintoe boei terboeka — kita kira dapat gratie — kita disoeroeh keloear teroes mengadap kantoor director, dan disitoe kita lihat ambtenaar Belanda dan penggawenja Indonesia. Belakangan kita dikasi tahoe bahoea-itoe ambtenaar Belanda ada gouverneur di Molukken in zijn eigen persoon boeat ambil kita dan bawa kekapal poetih. s.s. “Sirius” speciaal oentoek ambil kita.

Dengan kapal terseboet kita dibawa ke Ambon, dan sampai ditempat itoe tanggal 2 November 1929. Satoe sergeant Belanda dengan auto soedah papakan itoe kapal poetih didekat goedang arang. Keadaan kita semoea sangat koeroes dan peotjat, ma’loem dalam perdjalanan dihoetan menanggung sengsara jang amat heibat. Selain dari patjet (lintah besar) kan beriboe-riboe banjaknaya dalam rawa diperdjalanan kita, berdjalan dilaoetan, sangoe jang sangat soesah.

Penghidoepan dalam tahanan

Kita orang soedah diperiksa dikantoor ass. Resident. Dari boei diangkoet dengan tangan diborgol sebagai pendjahat biasa.

…

Djangan orang boeat beli pakaian, bpeat beli tembako sadja tidak biosa. Saban hari kita orang dapat roko tjengkeh,masing masing lima batang.Kalau mandi tidak pakai saboen. Toga boelan kortang lebih dalam tahana baroe dapat bako 3 kali.Sekali 2 pak, deoea 1 pak dan ketiga 2 pak. Itoe tembako ada tembako “Warning”.

Poen saboen dapat soedah tida kali, saban-saban satoe batang (saboen beko). Itoe semoea “barang poen katanja ada loear dienst, melainkan dari kebaikannja cipier.

Hingga ini sa’at kita masih dalam tahanan di Amboina.

Reference

Schoonheyt, L.J.A. Boven-Digoel. 1936. N.V. Koninklijke Drukkerij de Unie, Batavia